From ‘Lost Tribe of Everton & Scottie Road’ by Ken Rogers (book published 2010)

James Atherton built many of the fine mansions that once sat atop Everton Ridge. He was the driving force behind the building of St George’s ‘Iron’ Church. Atherton was an active shareholder in various Liverpool shipping companies. It is also said that he purchased a principals’ share in a slave ship called the Irene. There appears to be very little evidence to support the latter claim, not least because Atherton’s name does not appear in the “Lists of the Company of Merchants trading to Africa” for the late Eighteenth and/or early 19 Centuries. However, this does not prove or disprove any possible link with slavery.

Slave trading ventures were often agreements forged between up to a dozen individuals, some providing finance while acting as ‘sleeping’ partners. What is beyond debate is that during the first decade of its existence and before the ‘Bill for the Abolition of Negro Slavery’ was passed, in 1833, the St. George’s Church registers contained several references to slaves.

This information is confirmed in R.F. Mould’s informative history of the Iron Church:

26.10.1817: Charles Wallace, an African negro boy servant to George Seeley, late of Brazil, now of Everton.

18.2.1818: Nicademus John Nickolas, born in Santa Cruz, said to be 23 years old and a servant.

20.5.1818: Antonio Samuel Wylie, born in Mozambique and carried to Brazil as a slave, a servant of John Wylie.

15.11.1818: Samuel Barnes, born a slave in the island of Antigua, a gent’s servant.

12.4.1824; Charles, an African negro bought at Buenos Aires, about 21 years old, servant to Fred Dickson.

I’m intrigued to know whether these servants of the Everton gentry ultimately integrated more freely into the community post-1833. Are any of their ancestors still in Liverpool using the names Nickolas, Wylie, or Barnes? Slaves often took the names of their masters, as was the case with Antonio Samuel Wylie who was the servant to John Wylie.

If you’ve visited Liverpool’s incredibly moving International Slavery Exhibition at the Albert Dock, you will be aware that the town’s ships and merchants dominated the transatlantic slave trade in the second half of the 18th century. The Slavery Museum’s informative website tells us that the town and its inhabitants derived great civic and personal wealth from the trade, which laid the foundations for the port’s future prosperity.

The growth of the trade from Liverpool was slow but solid. By the 1730s, about 15 ships a year were leaving for Africa and this grew to about 50 a year in the 1750s, rising to just over a 100 in each of the early years of the 1770s. Numbers declined during the American War of Independence (1775-83), but rose to a new peak of 120-130 ships annually in the two decades preceding the abolition of the trade in 1807.

Probably three-quarters of all European slaving ships at this period left from Liverpool. Overall, Liverpool ships transported half of the 3 million Africans carried across the Atlantic by British slavers.

The precise reasons for Liverpool’s dominance of the trade are still debated by historians. Some suggest that Liverpool merchants were being pushed out of the other Atlantic trades, such as sugar and tobacco. Others claim that the town’s merchants were more enterprising. A significant factor was the port’s position, with ready access via a network of rivers and canals to the goods traded in Africa – textiles from Lancashire and Yorkshire, copper and brass from Staffordshire and Cheshire, and guns from Birmingham.

Although Liverpool merchants engaged in many other trades and commodities, involvement in the slave trade pervaded the whole port. Nearly all the principal merchants and citizens of Liverpool, including many of the mayors, were involved. Thomas Golightly (1732-1821), who was first elected to the Town Council in 1770 and became Mayor in 1772-3, is one example.

Several of the town’s MPs invested in the trade and spoke strongly in its favour in Parliament. James Penny, a slave trader, was presented with a magnificent silver epergne in 1792, for speaking in favour of the slave trade to a parliamentary committee.

It would be wrong to attribute all of Liverpool’s success to the slave trade, but it was undoubtedly the backbone of the town’s prosperity.

The last British slaver, the Kitty’s Amelia, left Liverpool under Captain Hugh Crow in July 1807. However, even after abolition, Liverpool continued to develop the trading connections which had been established by the slave trade, both in Africa and the Americas.

We now think of Liverpool as a truly international city, a melting pot of humanity inspired by our rich port heritage.

My own family history research opened up a fascinating link with the Chinese communities of Liverpool and Birkenhead, at the start of the 1900s, and you suddenly view and review the past in a different way.

I would like to think that Everton’s slaves – Wallace, Nickolas, Wylie, Barnes and Charles – were able to integrate into the working-class landscape of 19th Century Liverpool. However, poverty at that time meant that thousands were engaged in a daily battle for survival, regardless of colour or race. Indeed, the overcrowding and suffering in some of the old Everton courts (densely packed and over-crowded houses, around a communal yard) in the mid -1800s was a huge problem. The residents, living in atrocious conditions, were all slaves in their own way to the circumstances they found themselves in. My great grandparents lived in one of these courts in city centre Moorfields.

You can’t change history, but at the same time you can acknowledge and regret the fact that our great city, at a certain point in time, built much of its wealth on the slave trade and the exploitation of the working-classes.

It was intriguing, but not surprising to see this manifesting itself in the records of one of our most famous local churches.

The irony that James Atherton and other merchants were able to invest in a new church community in Everton, having made their fortunes in no small way from links with slavery, would seem to be a contradiction of everything they stood for.

Equally, the fight to end slavery unfolded in their lifetimes, something we hope they embraced.

Atherton officially retired from business in 1823, aged 53. He was now a “wealthy gentleman” and described in J.A. Picton’s Memorials of Liverpool as being:

“An ardent, bold and daring character . . . everything he undertook was carried out on a scale of magnificence, being always occupied with a variety of schemes for improvement and progress.”

This would be highlighted again when, in 1830, Atherton finally left his prestigious Everton address on Lodge Lane (Northumberland Terrace) to cross the river to inspire the new town of Black Rock (New Brighton). He was clearly a man who got things done for he established the first ferry service from Liverpool to New Brighton, and what an initiative that was.

Atherton’s final decade in Everton had been beset with personal tragedy. James and Betty lost three sons (James Junior, Charles and Henry Regent, within just a few years of each other, aged 19, 21 and 20. Possibly these painful memories were the catalyst for James’ bold move across the Mersey, but I doubt it. The man was a visionary who was always looking for new horizons.

On January 24, 1832, his son-in-law, William Rowson, paid a £200 deposit to John Penkett for the purchase of the New Brighton Estate, being £100 each for himself and his father-in-law.

Atherton wasn’t a true Everton boy, but he had stamped his mark on the district in a massive way.

You could argue that he saw the wind of change coming (or rather the human ants starting to crawl in their thousands up ‘The Hill’, including my great grandparents). These new working-class Evertonians, many of them just above the poverty line, began to swarm all over God’s little acre which is how Atherton must have initially perceived his new, hilltop home.

The green slopes were disappearing by the day, replaced by densely-packed terraced streets as far as the eye could see. Indeed, the Nether fields were now dissected by the imposing Netherfield Road North & South. This busy thoroughfare stretched from Everton Valley at one end to Shaw Street at the other, where the impressive Liverpool Collegiate School would soon be built (1843).

After moving to New Brighton, Atherton would have been able to see Everton and St. George’s Church as he looked across the Mersey. I’m sure the sight of the soaring Everton ridge always made the hairs on the back of his neck stand up whenever he took in that view.

Fittingly, he was buried in the St. George’s churchyard in 1838, although there is no mention on his gravestone that he was the visionary behind the building of the church; the view from which remains one of the city’s great vantage points.

Ironically, to defend his privacy, he wouldn’t allow the church entrance to face his mansion. His gravestone is now just a few feet away from that same door. No privacy needed in death with his unobtrusive headstone standing anonymously against a nearby wall.

Like Atherton, I eventually found myself ‘across the water’. Not surprisingly, I was drawn to the mirror hill of Everton, that of the equally historic Oxton. I often go down to the river on the Birkenhead side, and my first instinct is always to look towards the summit of Mount Everton and the Iron Church where I sang in the choir and went to Sunday School. It will always be my spiritual home

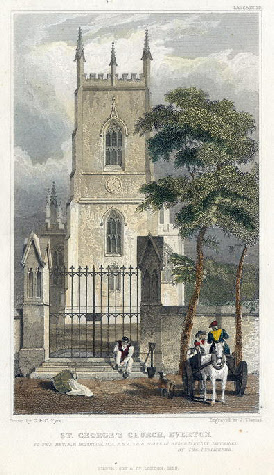

St George’s Church 1800s