Stroll across our spectacular green space and feel supremely proud of historic Everton

By KEN ROGERS – Author of the ‘Lost Tribe of Everton’ books

Well, it has been quite a journey for every member of the ‘Lost Tribe of Everton & Scottie Road’ since the two books, highlighting the 1960s to 1980s clearances that affected over 150,000 people, were published in 2010 and 2012.

Since then we have had a succession of annual street reunions, using the historic St George’s ‘Iron Church’ as our base and 2018 marks the ninth such gathering of the clans.

Your freely submitted memories along the way have inspired me, made me laugh and stirred my emotions. Most of all, they have made me feel very proud.

The spectacular and modern Everton Park, of course, sits atop 110 of our former terraced streets whose foundations can tantalizingly be found just a few feet under the surface of this very special linear green pace. We proved this when Friends of Everton Park supported official archaeological digs to find the former St Benedict’s Church on Heyworth Street, and Queen’s Head Hotel in Village Street, the latter being the birthplace of big time football on Merseyside.

In this section of our website we invite you to join us on a walk into the past across the summit of Mount Everton. Our walk begins in St. George’s churchyard. Here you should stand and imagine how our ancestors sent messages warning of imminent danger, possibly the arrival of an invading foreign army on our shores. The lighting of the Everton Fire Beacon was the ancient version of sending a text on your mobile phone.

In many respects, it was equally effective because messages could be flashed across the country extremely quickly via these hilltop sites. Read on to find out more . . .

![]()

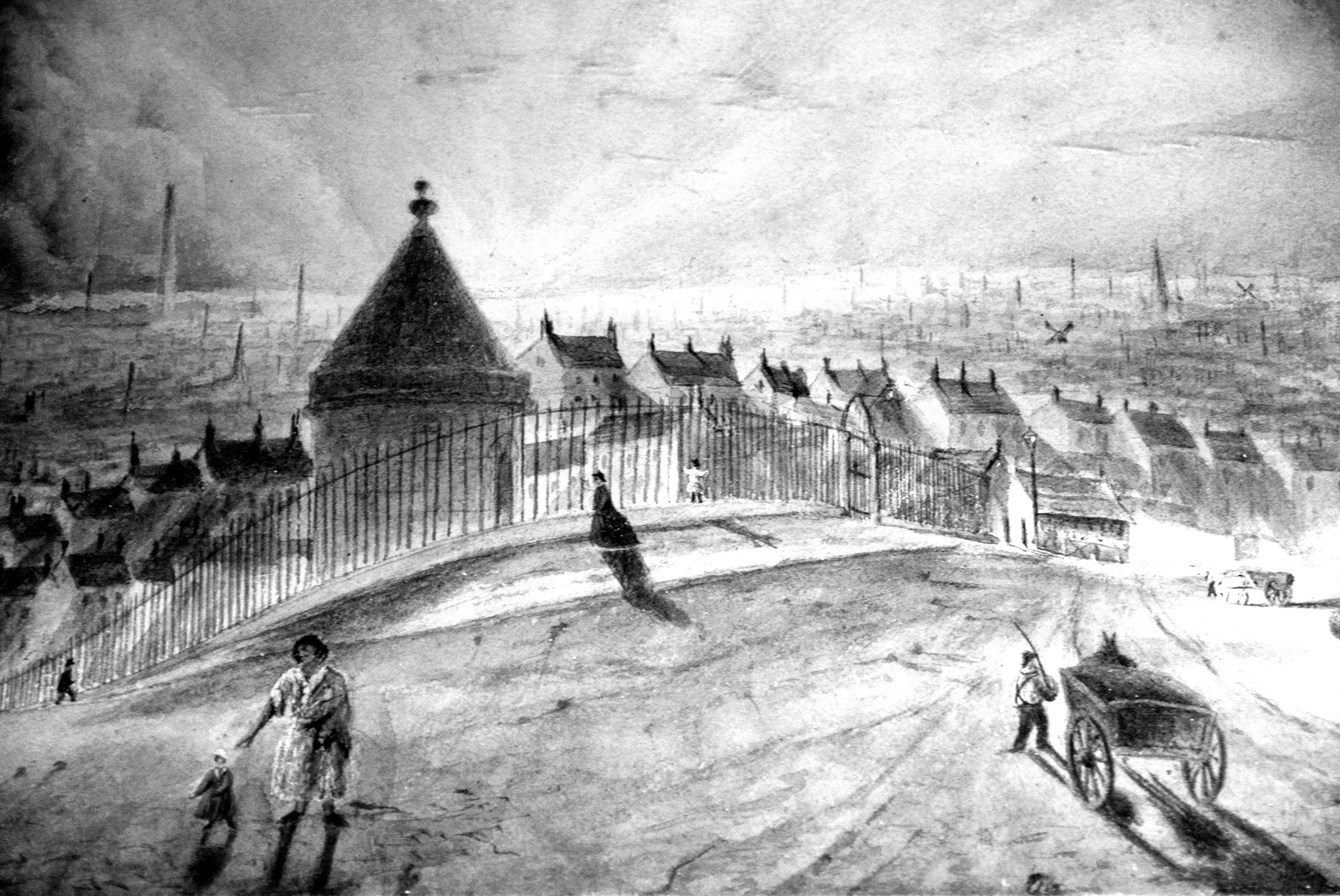

The Everton Fire Beacon (1230-1803).

The Everton Beacon was the tallest building in ancient Everton, commanding the highest point on the ridge. It was built by Ranulf – the Earl of Chester, the first baron of Liverpool – on the site of the present St. George’s Church during the reign of King Henry 111 (1207-1272). When lit, the Beacon could be seen for miles around. Fire Beacons occupied high ground right across the country to warn of imminent danger. Indeed, the Everton Beacon and others like it were lit when the Spanish Armada was sighted off the English coast during the reign of Queen Elizabeth 1st. For centuries, Everton’s famous landmark was a feature of both the local geography and community life. Hundreds of people would gather below it to picnic and relax in what is now Everton Park. Towards the end of the 18th century, the tower was becoming unsafe and it was severely damaged on a stormy night in 1803. Twelve years later the site had been cleared to make way for the new St. George’s Church, but the path approaching it from the north side would ultimately become Beacon Lane to mark an historic Everton landmark.

St. George’s ‘Iron Church’ (1814).

The Fire Beacon site would make way for one of Everton’s most famous landmarks. St. George’s Church was the vision of merchant James Atherton (1770-1838) who bought a sizeable piece of land across the top of Everton Ridge from the St. Domingo Estate. Atherton commissioned a string of luxurious hilltop mansions, each with spectacular views of the River Mersey and the Wirral Peninsula beyond. He recognised the need for a church to serve the needs of the growing local merchant population and raised £11,500 by public subscription.

The church was completed in 1814 on the old Beacon site, directly opposite Atherton’s own mansion. The innovative ideas of church architect Thomas Rickman (1776-1841) included a cast iron frame clad with local sandstone. The revolutionary use of iron would ultimately lead to the erection of much higher structures, like Liverpool’s classic Liver Building, and many of the early skyscrapers across the Atlantic in places like New York.

From his garden, Atherton could see a ‘Black Rock’ across the river to the North West and this would take him ‘over the water’ to plan the famous Mersey seaside resort of New Brighton. His love of Everton never waned. On his death, Atherton was brought back to St. George’s and buried in the churchyard.

The Victoria Cross

Victoria Cross heroes in the heart of Everton.

From St. George’s Church, you should now walk into Everton Park and take the top path to a point beyond the old Thistle Pub, now May Duncan’s. Here stood the old Heyworth Street School which is just one of the sites in Everton with links to the Victoria Cross, thehighest and most prized military decoration any member of our armed forces can be awarded for showing courage in the face of the enemy. Two words on the Victoria Cross say everything about those who have earned this ultimate accolade: FOR VALOUR.

The VC takes precedence over all other orders, decorations and medals and may be awarded to a person of any rank in any service and to civilians under military command.

Introduced on 29 January 1856 by Queen Victoria to honour acts of valour during the Crimean War, the medal – at the time of writing – has been awarded 1,356 times to 1,353 individual recipients. Only 13 medals, nine to members of the British Army, and four to the Australian Army, have been awarded since the Second World War, demonstrating that this is a medal that is truly one of the most treasured of accolades anywhere in the world.

Sixteen VC’s have been awarded to Liverpool heroes, a record that demonstrates the wider courage, fortitude and character of the men of our city who have never been found wanting when their country has needed them, something that is still evident today in places like Afghanistan and previously in Iraq, the Falklands, and other modern theatres of war.

One thing that should fill us with personal pride is that four of those 16 Victoria Crosses were won by men with massive links to the very heart of Everton:(David Jones; Paul Aloysius Kenna, Gabriel George Curry; Albert White.

Sgt. David Jones VC went to Heyworth Street School. He would join the King’s Liverpool Regiment whose military courage brought reflected glory on every inner city youngster who attended Heyworth Street and looked up at the famous brass plaque on the school wall that declared:

To the memory of

Serg. David Jones VC

The King’s (Liverpool Regiment)

An old pupil of this school, who was awarded the Victoria Cross during the Great War for his inspiring courage and cheering example. When his officers, having all fallen, he took command, captured an advanced position on the Somme front, and in spite of the fiercest counter attacks, held it for nearly three days, until relieved. He was killed in action three weeks later on October 7th1916.

“Qui ante diem, perit

Sed miles, sed pro patria”

The above translates to:

“They died before their time

As soldiers – and for their country”

A fantastic publication entitled: Liverpool Heroes (Book 1), the stories of 16 Liverpool holders of the Victoria Cross, edited and researched by Ann Clayton, with further research by Sid Lindsay and Bill Sergeant further reminds us of the ‘Valour’ of these military heroes.

In the book foreword, Bill uses a biblical quotation from John 15.13: ‘Greater love hath no man than this; that a man lay down his life for his friends’.

It has been used on the headstones of many soldiers, notably one of Liverpool’s most respected war heroes Noel Chavasse VC and Bar (in other words a double Victoria Cross recipient).

The words sum up perfectly that moment of selfless courage when someone puts themselves right in the firing line with no regard to their own safety.

In 1901, the Jones’ family were living at 25 Elmore Street, Everton. On 27 May, 1915, the young David Jones married Elizabeth Dorothea Doyle, and they went to live at 87 Heyworth Street. Jones won his VC on the night of 4/5 September 1916.

As you stand close to his old school, you should now remember Paul Aloysius Kenna who was born half a mile down the hill from Heyworth Street, at Oakfield House, 22 Richmond Terrace, on 16 August 1862. At the age of seven, Paul attended St. Francis Xavier’s School in Salisbury Street. He was later commissioned as a Lieutenant in a Militia Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry.

Kenna would eventually join the 21stLancers, stationed in India, and he became the leading gentleman rider in India. He found himself in Ireland in 1895 where he rescued a man from the River Liffey in Dublin, receiving the Royal Humane Society’s ‘Vellum Testimonial’. In 1895 he was promoted to Captain, and the following year went with the Lancers to Egypt. He found himself part of an Anglo-Egyptian Expeditionary Force marching on Khartoum where the legendary British Governor of the Sudan, General Charles Gordon, had been slaughtered.

On 2 September, 1895, the 21stLancers were ordered to advance between a prominent hill and the River Nile to harass the enemy’s flank, believing they were facing just a few hundred Dervishes. The Lancers advanced at a gallop. Suddenly 3,000 white robed Dervishes appeared on the ridges on their flank and the Lancers were trapped and under severe enemy gunfire.

There was no option but to wheel round and cut their way back through the massed enemy ranks. The tribesmen targeted the horses, leaving the unseated soldiers to fight for their lives on foot. Kenna, second in command to Major Fowle in one of four squadrons, used his superb horsemanship to get through. The Lancers dismounted and pinpointed withering fire on the Dervishes who, despite their numbers, retreated with 2,000 repelled by 300 Lancers.

It was said that Kenna and B Squadron went into the most densely packed area of the enemy line, highlighted by the fact his squadron won all three of the VC’s awarded that day.

At one point in the mayhem, Kenna stopped his horse and used his revolver to enable the dismounted Major W.G. Crole-Wyndham to climb up behind him. The unsettled horse then threw both Lancers after 50 yards. Kenna retrieved the horse while Crole-Wyndham escaped on foot and both rejoined the line.

The ‘Liverpool Heroes’ book reveals that in December 1906 Kenna was appointed aide de camp to King Edward V11. Sadly, there would be no happy ending for this brave former SFX boy. He became Brigadier General of the Midlands Mounted Division, but was shot by a Turkish sniper’s bullet on 29 August 1915 and died the next day.

Gabriel George Coury VC was born in Sefton Park, but is another SFX boy. He attended the Everton school between 1901 and May 1907. At the start of the First World War, he enlisted as a Private in the King’s (Liverpool) Regiment. After training, his leadership qualities were recognised when he was made a 2ndLieutenant in the South Lancashire Regiment. He went to France in 1915 with his regimented designated a Pioneer battalion and the following year found himself in the middle of the disastrous Battle of the Somme, a war of attrition in the trenches.

On 5 August Coury was in a trench under heavy bombardment when a ton of explosives ignited. There was panic amongst the troops who believed the Germans were making a bomb attack. As many tried to leave the trenches, Coury picked up a rifle and bayonet and took charge to get the men back in position.

This highlighted his leadership qualities. His moment of ‘Valour’ was reported by the London Gazette:

During an advance he was in command of two platoons ordered to dig a communication trench from the old firing line to the positions won. By his fine example and utter contempt for danger, he kept up the spirits of his men and completed his task under heavy fire. Later, after the Battalion with whom he was working suffered heavy casualties and the Commanding Officer had been wounded, he went out in front of the advancing position, and in full daylight, in full view of the enemy, he found the Commanding Officer and brought him back to safety over ground swept with machine gun fire. He not only completed his original task and then saved the Commanding Officer, but he also succeeded in rallying the attacking troops when they were shaken, and leading them forward.

Coury was only 20 years of age and was only eight years out of SFX School. The boy had become a very brave man and an eye witness declared to the Liverpool Daily Post that he was “the bravest officer I ever served under.”

The fourth Victoria Cross with an Everton link was won by Albert White. He was born in Kirkdale, at 54 Lamb Street, but his father educated him at Everton Terrace School in the heart of what is now Everton Park. On 23 October 1915 he enlisted with the Royal Army Medical Corps, and was then transferred to the 2ndBattalion of the South Wales Borderers.

In 1916, Albert found himself in France with his Battalion, now part of the 87thBrigade in the 29thDivision. Like Coury, he was at the deadly Battle of the Somme. He was promoted to Sergeant and his Battalion was told to attack the strongly defended German position at Beaumont Hamel where they had constructed strongly fortified dugouts.

White and his men faced devastating machine gun fire and the battalion lost 11 officers with 235 men killed or missing and a further four officers and 149 men wounded. This was from a total of 21 officers and 578 men.

‘Liverpool Heroes’ tells us that the 2ndBattalion had to be reformed and saw fresh action in 1917 at Monchy-le-Preux where Albert White earned his VC at the Battle of Arras. Despite being under heavy enemy fire, White and his men dashed towards the enemy position. During the ‘rush’, a concealed German machine gunner opened fire, threatening the advance. Sergeant White raced ahead of his men to capture the gun. He flew at the enemy, shooting three and bayoneting a fourth, but was killed as he got within yards of the gun.

Doesn’t it make you feel fiercely proud to come from the city of Liverpool? If, like me, you are from Everton, doesn’t it fill you with extra pride when you consider the strong links of these particular four heroes with our famous district?

We salute Paul Aloysius Kenna VC DSO; Gabriel George Coury VC; David Jones VC; Albert White VC.

* We thank the authors of ‘Liverpool Heroes: The stories of 16 Liverpool holders of the VC’for their tremendous research and heartfelt input into a book that we would commend you all to read to gain a fascinating insight into the courage of Liverpool’s VC heroes.

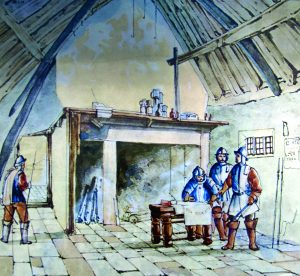

Prince Rupert’s Old Camp Field (1664)

You don’t have to move very far from your position on the old Heyworth Street School site to get a feel for one of the most remarkable episodes in the history of Everton. Indeed, you are now standing in the middle of a giant English Civil War Royalist army headquarters that spread out across the ridge at this point. Obviously, Heyworth Street itself was nothing more than a path in the 1600s.

It was Prince Rupert of the Rhine who brought a 10,000 strong Royalist force to Everton in May 1664. Liverpool’s population was just 1,000 at the time. The Castle and Town Hall in the town below had been taken by the Royalists in 1642. The Parliamentarians reclaimed the Liverpool the following year and Everton would now become the springboard for a fresh Royalist attack in the name of the King Charles 1.

The Royalist army – with horses, munitions and supplies – set up camp across the ridge at this point with uninterrupted views of the town below.

Rupert claimed Liverpool was ‘But a Crow’s Nest that a parcel of boys could take.’ However, he was surprised by the resistance and lost 1,500 men before finally breaching the defences with 360 defenders shown no mercy. The Royalists plundered the town’s gold bullion. Legend has it that Rupert buried it in a tunnel near to his Everton Village headquarters, meaning to claim it at a later date. However, the Parliamentarians recaptured the town before the year was out. The gold horde was never found despite the efforts of many treasure hunters and could still lie below the steep slopes of Everton.

The greatest view in Liverpool.

You now take the park path to the viewing platform and car park a few hundred yards away with its commanding views across the city and the river beyond. This gives you a complete understanding as to why Prince Rupert chose this spot to plan his deadly attack on Liverpool.

Everton ridge may only be 245 feet above sea level, but the panorama from left to right (south to north) is a sight to behold.

The horizon is dominated by the Snowdonia mountain range featuring the highest mountain in Wales (Snowdon 1,055 metres). The Wirral Peninsula bridges the middle distance from the Mersey to the unseen River Dee. This is a powerful watery border between England and North Wales. On the far side of the Mersey you can see the large grey box-like structure that is the globally famous Cammell Laird shipyard, built in 1828. This stands in Birkenhead which, with Seacombe to its right, is part of the triangular route of the renowned Mersey Ferries.

The Mersey has always been at the heart of Liverpool’s development. The town emerged from a small and muddy pool and creek in 1190 to become the second city of the British Empire as the 20thcentury dawned. To your left, the distinctive Anglican and Metropolitan Roman Catholic Cathedrals rise up. The world famous Liver Building and the Radio City Beacon Tower can also be seen. Everton Terrace, with its many large Victorian residences, ran below here into the heart of the old Everton Village.

‘Clearances’ create the ‘Lost Tribe of Everton’

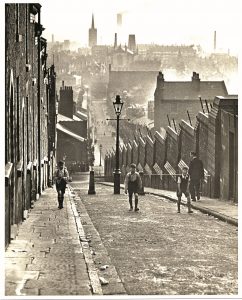

Remaining at this viewing point, forget the view for a moment, if that is possible, and imagine what lies unseen beneath the modern Everton Park. You are in the heart of what was once a remarkable concrete jungle of back to back terraced houses, standing in hundreds of steep streets sweeping down from this ridge.

This was a sight to behold prior to the 1960’s when the ‘clearances’ changed the face of Everton forever. Over 125,000 residents were forced to leave this historic district for new towns and estates on the outer limits of the city. The clearances are now part of Everton folklore, captured in a song written by Harry and Gordon Dixon entitled Back Buchanan Street.

‘We’ll miss the Mary Ellens and me Dad’ll miss the docks.

And me Gran will miss the washouse where she washed me Granddad’s socks

Don’t wanna go to Kirkby, or Skelmersdale or Speke

Don’t want to go from all we know in Back Buchanan Street’

Back Buchanan Street did not exist, but could have been any street in Everton, the world-famous Scotland Road area, or any other inner city districts where open-door heartland community living made people fiercely proud of their close friends and neighbours.

This heritage trail marker would be an opportunity to remember everyone you loved and who might have never known anything but these concrete streets. Typical was Copeland Street near here where my grandparents Tom and Emily Rogers lived, small terraced properties that stood for 80 years before the City Council invoked a radical new beginning for Liverpool 5.

‘Streets in the skies’

As the 1960’s ‘clearance’ programme swept aside the old terraced streets of Everton, this ridge and the land below it became the focal point for a social experiment in High Rise living that would once again dramatically change the face of this famous district. In the early 1800’s, this hill had been a farming area and a green and pleasant oasis for the rich merchants who built their large mansions and villas here. A working class army, swollen by many immigrants fleeing the devastating Irish Potato famine of the 1840’s, then swept up the hill in the mid-1800’s to claim ‘Mount Everton’ for their own.

The 1960’s ‘clearances’ brought this phase in Everton’s social history to a dramatic close. The terraced streets were replaced by 17 High Rise monoliths that stood like upturned dominoes above and below Netherfield Road that runs right and left just 50 yards below the main viewing platform.

Netherfield Road North & South was also famous for the Orange Lodge bands that would march along its full length, notably on 12 July, when Everton bristled with fervour, noise and passion.

The district changed dramatically following the development of the High-Rise giants, described by the architects who didn’t have to live there as ‘streets in the skies’. The only ones still standing are Crete, Candia, Brynford and Milburn. Others that became famous in their own way included the Braddocks, Mazzini, Cavour and Garibaldi, John F. Kennedy Heights, St. George’s Heights, and Haigh, Crosby and Canterbury (notoriously dubbed the ‘Piggeries’) as High Rise Heaven deteriorated over 20 years into High Rise Hell. Everton was part of a social experiment that has resonance to this day as the modern residents continue to fight for the betterment of their famous district.

Shopping heaven along ‘Greaty’

Looking down the fill from this point can be seen what, for half a century and more, was described as the ‘Petticoat Lane’ of the north – Great Homer Street. This was an open-all-hours, shop ‘til you drop experience for the cacophony of visitors who would wander in their thousands from Kirkdale Road at one end to Cazneau Street at the other where the legendary open air market was a sight to behold.

Always jam-packed, the market contained a rich mix of local characters and international visitors. Many worldly-wise sailors with an eye for a bargain would eagerly carry goods back to ships on the docks. There were Indians and Africans, Chinese and Europeans, buying second-hand suits, hats, and even old bikes.

Greaty’s most important customers were the working-class locals from Everton, Scottie Road, Vauxhall Road, and the surrounding terraced street districts. ‘Greaty’ was a one-mile strip of shopping heaven with two famous department stores – Sturla’s, plus one of the city’s first Woolworth shops. Its real appeal was linked with its distinctive little stores. There were 17 grocers and 27 butchers with over 190 separate businesses.

Like its near neighbour Scotland Road, ‘Greaty’ had its share of corner pubs, 17 in all. Every one of them would ultimately fall victim to the 1960’s housing clearances.

Great Homer Street’s famous shopping past is part of a modern regeneration plan that will see life breathed back into a road that was synonymous with every-day life in the district of Everton.

The world-famous ‘Scottie’.

The next horizontal thoroughfare beyond ‘Greaty’ is the world famous Scotland Road.Known worldwide as ‘Scottie’, it once featured a pub on every street corner. With is busy bus and former tram route, it played the powerful masculine father to the inner district heartland district of Everton on one side and Vauxhall on the other. Up to the end of 2009, you could find the first ‘Everton’ district sign on Scottie between its junction with Leeds Street and the slip road to the Kingsway Mersey Tunnel. The sign has now disappeared behind further boundary changes, but Scotland Road is inextricably linked with this area.

These days ‘Scottie’ serves as an entrance and departure point for the second Mersey Tunnel (Kingsway) and remains the city’s main arterial route to the north. But ‘Scottie’ was not about traffic or buildings. It was about the people who occupied densely packed streets to the east and the west. This community actually felt as if they belonged to their own distinctive ‘Republic’. They included thousands of families with strong Irish Catholic links who came pouring into the district in the mid-1840’s when the nearby dock area was a massive base for those immigrants and emigrants seeking to escape from the devastating effects of the Irish Potato Famine that led to one of the biggest migrations of people the world has ever seen.

Many chose to stay in this area as an inner city concrete jungle of houses swept up to the very summit of the hill. This swelled the congregations of churches like the famous St. Anthony’s which is clearly visible from the higher reaches of Everton Park, still standing proudly on Scotland Road.

The slum clearance plan that gathered pace at the start of the Sixties wrecked what many believed was the greatest community in Liverpool.

St. Francis Xavier Church and College (1843).

Looking south from Everton Park, you can see the prominent spire of St. Francis Xavier in the heart of what was once the biggest Roman Catholic parish in the United Kingdom with over 13,000 parishioners. Initially, a small Jesuit College was opened in Everton in 1843, followed five years later by the Church, designed by John Joseph Scholes. The tall, elegant spire, added in 1883, remains a prominent local landmark.

The establishment of this leading Catholic church – run by Jesuits – was a major social advance in the conservative, Protestant, Victorian Liverpool of that time. Between the planning of the new church and its opening, the Irish Potato Famine had inspired over two million Irish men, women and children to seek a new life in America – most using Liverpool as a transit port.

The town was swamped with tens of thousands of Catholic refugees. As a result, SFX church, designed to hold 1,000 people, was now too small.The beautiful Sodality Chapel – designed by Edmund Kirkby – was added in 1888. Followings its inception, SFX built a variety of schools, including SFX College, which was opened in 1843 as the first Catholic Secondary Grammar Day School in the country.

Schools for the Catholic poor of the parish were also established. SFX remained a large parish until the 1960s, at which time the Grammar School moved to Woolton in the southern suburbs of the city as the population of Everton declined following the ‘clearances’.

Collegiate School (1840)

Collegiate School, with its dramatic facade, can also be seen from Everton Park, standing opposite the spire of SFX. Collegiate was built in 1840, one of the first public schools in the country. It preceded such eminent educational establishments as Marlborough, Cheltenham, and Wellington.

It was designed by Harvey Lonsdale Elmes, aged only 26 at the time, and who was also the original architect of the city centre St. George’s Hall. The main entrance porch is an imposing Tudor-style arch, above which is carved the coat of arms of the school. The Collegiate never conformed to the many stereotypes of other 19th century public schools, principally because few similar establishments were situated in such urban areas, and its only boarding pupils lived locally in the homes of approved schoolmasters. As Collegiate’s reputation grew, so did its pupil numbers and income.

In the 20th century, the school ceased operating as a fee-paying establishment and it was taken over by the Local Authority, soon becoming a respected state grammar school. However, from 1970 the final years of the school’s life were a period of steady decline in tandem with the local area. It changed into a comprehensive school, but the end was clearly inevitable.

In 1985, a fire severely damaged the building, and completely gutted the assembly hall. Collegiate has been converted into a private apartment complex, retaining the magnificent façade. The original octagonal assembly hall had been the first home of the Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra. It is now a delightful enclosed garden.

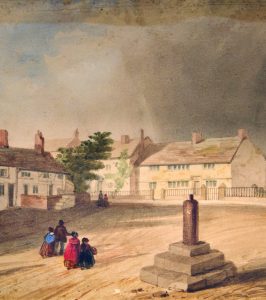

Village Street

Using the famous Everton Lock-Up Tower as a marker, the Heritage Trail walk will now take you from the spectacular viewing platform down into the heart of the ancient village of Everton, first recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086. The village was known as ‘Evreton’ in 1094; as ‘Euerton’ in 1201; and as ‘Everton’ since the end of the 13th century. Whether the name Everton derives from the Celtic-Roman for ‘wild boar’ or is simply a shortening of Higher Town, the village has a fascinating history.

An image of the Lock-Up Tower looking up the hill was painted by famous artist Herdman and shows and idyllic scene on Everton Brow in 1878. Youngsters play around the Tower alongside the Everton Toffee Shop and Prince Rupert’s Cottage. Sheep and cattle graze in hillside fields and the hay-making indicates that this was a summer scene. Netherfield Road, immediately below the Tower, did not exist at this time.

The population of Everton had remained static for centuries, a settled and relatively isolated village. Even in 1801, the population was recorded as being only 499, and the Village grew up around an area that had previously been known as ‘Sandstone Hill’.

However, during the English Civil War, in the mid 17th century (1642-46), the tranquility and isolation of the village came to an abrupt end, and Everton suddenly took on a strategic importance.

Prince Rupert’s Cottage stood across a track, immediately to the right of the Lock-Up Tower as you look down the hill. It was named after Prince Rupert of the Rhine (1619-1682), the nephew of King Charles I (1600-1649). The Prince stood against the forces of Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) and organised the siege of Liverpool. He established his Royalist headquarters here on Brow Side. After the Civil War ended, Prince Rupert’s Cottage became an ordinary home once more and, for many years, it was occupied as a family home before being demolished in 1845.

The Everton Toffee Shop: Around 1690, another larger cottage was built next to Prince Rupert’s old cottage and it was here, in 1753, that Molly Bushel (1746-1818) began to make the boiled sweets she called Everton Toffee. This toffee was much prized, not just by locals, but also by the wealthier classes.

In 1783, Molly converted her house into a shop and began to expand her range of confectionery. Later, Everton Toffee, which continued to be made by Molly’s descendants, became a great favourite with Queen Victoria, who had batches of it regularly shipped to Windsor Castle.

The recipe had been given to Molly by its inventor, Doctor James Gerrard, a local physician and Town Council member. The Everton Toffee Shop was demolished in 1844. Everton Toffee is still produced although not to the original recipe. Everton Football Club’s ‘Toffee Lady’ mascot still throws sweets to the crowd at every home game (see Queen’s Head Hotel, Village Street).

The Everton Lock-Up Tower:As Everton began to expand, the centre of life in the village was around the village green and Molly Bushel’s Toffee Shop, and there was a significant rise in the numbers of visitors to the village. These people came to take the air, to buy the famous toffee, and to see Prince Rupert’s old Cottage. Eventually, there were so many day-trippers that, in 1787, it was considered necessary to build a local lock-up ‘to house drunks and unruly revellers overnight’.

This became a well-known landmark, sometimes called The Stone Jug, but also called ‘Prince Rupert’s Castle’ by locals although it was erected long after the Prince had gone. It is one of only two surviving village gaols in Liverpool, the other being located in the middle of Wavertree Village to the south of the City. In 1800, Everton had been described as ‘a pretty village with a view, which embraces town, village, plain, pasture, river, and ocean.’

Queen’s Head Hotel. Immediately behind the Lock-up Tower, the original Village Street, with its historic Village Cross, wended its way to the top of the ridge. Its main pub, the Queen’s Head Hotel, was the scene of an historic meeting in 1879 that led to St. Domingo’s Church Football team changing its name to Everton Football Club.

This heralded the start of the city of Liverpool’s remarkable football heritage. Everton FC became founder members of the Football League in 1888. Ironically, the club never played in Everton, its original pitch being in Stanley Park, while its main early headquarters was the current home of Liverpool FC in Anfield.

Everton FC built its present Goodison Park Stadium in Walton in 1892, a move that inspired the formation of Liverpool FC to signal one of the greatest rivalries in world football. However, Everton’s roots remain firmly in heartland Everton where it took its name, and from where the original St. Domingo’s FC drew many of its early players. The Everton lock-up tower is featured on Everton FC’s famous crest, confirming its powerful links with this site.

In less than a mile you have experienced some remarkable and contrasting local history stories.

WELCOME TO EVERTON AND ITS SPECTACULA PARK OF MEMORIES AND FOLKLORE.

For a more formal circular walk, please follow the Everton Park Heritage Trail with its 13 informative boards.